At Tekaroid, we have all seen those videos. Small delivery robots stuck at crossings or waiting patiently while the city moves around them. They have been circulating online for years, presented as proof that the future is already here. We keep seeing robot deliveries on screens, but rarely in person. If this technology has been ready for so long, why does it still feel almost invisible?

For nearly a decade, robot delivery has existed in a limbo between technological advance and public curiosity. Periodically, videos surface showing small autonomous vehicles calmly navigating sidewalks, carrying food or groceries without human involvement. This is not a trial. This is the future arriving early.

What followed, however, was not a city-wide transformation but a quieter, more selective outcome. Robot delivery did not disappear, yet it also failed to spread in the explosive way ride hailing or food delivery apps once did. Instead, it embedded itself into very specific environments, under very specific conditions, where space, economics, regulation, and public tolerance line up just enough.

To understand why, it helps to step away from promotional narratives and look at how these systems behave once they encounter real sidewalks, real people, and real constraints.

Autonomous last-mile deliver

Technically, what is often referred to as robot delivery belongs to a broader category known as autonomous last-mile delivery. These systems rely on small, electrically powered ground vehicles designed to transport goods over short distances, usually at walking speed, using cameras, lidar, ultrasonic sensors, GPS, and continuous remote connectivity.

They are deliberately conservative machines. Rather than improvising, they stop, wait, and escalate uncertainty to human operators. This makes them safer than many forms of autonomy, but also far more dependent on the environment around them. Their success is determined less by intelligence and more by context.

Companies such as Starship Technologies, Serve Robotics, Nuro, and Coco Robotics have each approached this challenge differently, but all share one assumption: last-mile delivery only works when uncertainty is tightly controlled.

How the idea first took shape

Robot delivery did not begin as a carefully defined solution to a specific problem. It grew out of a wider moment of confidence in autonomy. In the mid-2010s, progress in sensors and mapping made it feel as if navigation itself was becoming a solved challenge, something that could be applied almost anywhere.

Sidewalk robots fit that mood perfectly. Compared to autonomous cars, they seemed modest and manageable, a way to test autonomy in public without the political and technical weight of traffic. Putting them on sidewalks was not only practical but symbolic, a way to show that the future was already moving among people.

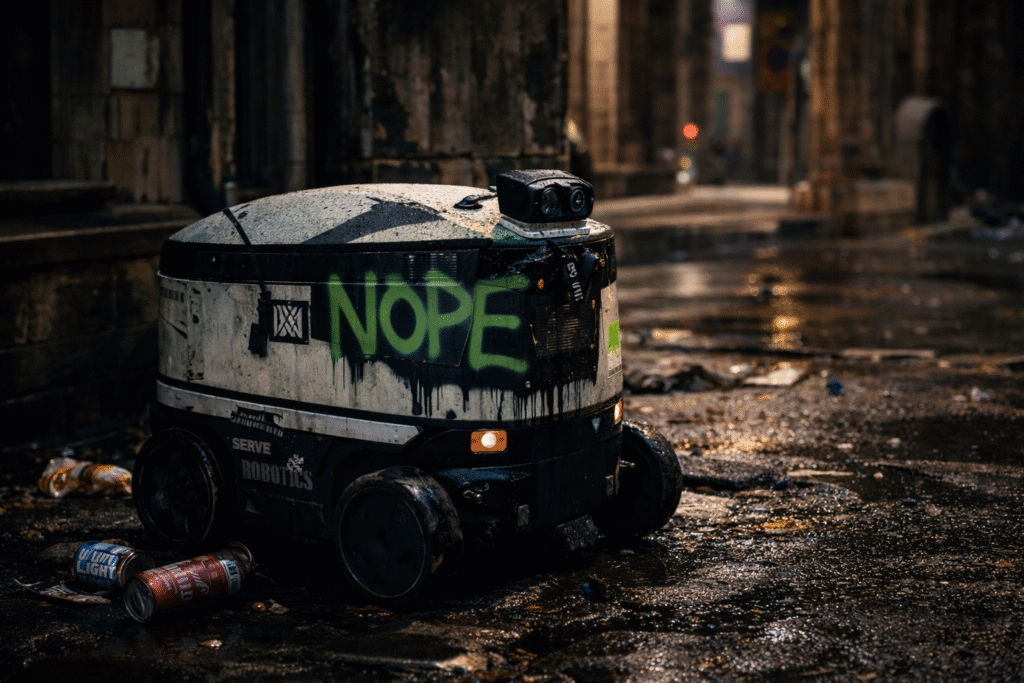

What followed exposed a blind spot. As robots became more visible, they stopped being background infrastructure and turned into objects of attention. The more people noticed the robots, the more they interacted with them. They filmed them, blocked them, tested them, questioned their presence, and in some cases, vandalising them. What was meant to normalise the technology revealed how fragile public tolerance could be.

The economic problem autonomous delivery tries to solve

The promise of autonomous delivery has never been about speed. It is about economics. In many delivery systems, the weakest point is the final stretch, where short distances, small orders, and waiting time combine into work that is expensive to manage and hard to optimise with human labour.

This is where delivery robots enter the picture. They are not meant to outperform couriers, but to handle the kind of deliveries that quietly erode margins. A robot does not care if an order is small, if the route is repetitive, or if the pace is slow. As long as it keeps moving and requires little supervision, its value comes from consistency rather than efficiency.

From the start, the ambition was limited by design. Autonomous delivery was never intended to replace human couriers at scale, but to take over the least attractive part of the system. The idea was not transformation, but stabilisation, removing friction rather than reinventing delivery altogether.

Where autonomous delivery works

The strongest evidence that autonomous delivery works comes from environments that reduce uncertainty rather than eliminate it. University campuses are the clearest example. Distances are short, routes repeat daily, traffic is limited, and pedestrian behaviour is relatively predictable.

This is where Starship Technologies focused its strategy, deploying fleets across campuses in the United States and Europe. These are not pilots. They are long-running operations with millions of completed deliveries. Their success is not dramatic, but routine, which is precisely why it matters.

Planned residential areas represent a second successful category. In the UK, Milton Keynes became one of the longest-running testbeds for autonomous sidewalk delivery. Its wide pavements, modern layout, and lower pedestrian congestion made it compatible with slow-moving machines.

In both cases, the technology did not adapt to the environment. The environment already suited the technology.

Where it struggled or failed

Dense urban centres exposed the limits of the model. Trials in cities such as San Francisco and parts of New York encountered resistance driven by sidewalk congestion, accessibility concerns, and public discomfort. In San Francisco, local authorities imposed strict limits on delivery robots, effectively preventing large-scale deployment.

These setbacks were not caused by technical failure. The robots could navigate. The problem was spatial and social. Narrow pavements, unpredictable pedestrian flows, and constant construction turned every delivery into a negotiation the machines could not resolve efficiently.

In the UK the story has been more mixed. Services such as Starship robots have found limited success in towns with wide sidewalks and predictable pedestrian movement. At the same time, they have generated complaints in places where infrastructure was never designed for autonomous machines. In Milton Keynes, for example, cyclists have occasionally criticised the robots for blocking paths.

Across these contexts, robot delivery did not struggle because autonomy was underdeveloped, but because public space proved resistant. Sidewalks are shared social environments, not neutral testing grounds. Curiosity, obstruction, and in some cases vandalising the robots became part of everyday operation, exposing the gap between what machines can technically do and what streets are willing to tolerate.

Regulation as the silent constraint

Sidewalks are public infrastructure, and most cities are reluctant to let private logistics systems occupy them without strict oversight. As a result, regulation has quietly become one of the main forces shaping where robot delivery can and cannot exist.

In practice, this means there is no single legal framework to navigate. In the United States, rules change from one city to the next, with permit systems, fleet limits, and operating restrictions that make large scale deployment difficult. European cities have tended to move even more cautiously, placing greater emphasis on pedestrian priority and accessibility than on rapid experimentation.

The consequence is a fragmented path forward. Autonomous delivery is not blocked by one decisive regulation, but by hundreds of local interpretations of public space. Expansion depends less on technological readiness than on whether a city is willing to redesign its sidewalks around machines.

From novelty to infrastructure

Autonomous delivery started as something unusual. Seeing a small robot on the sidewalk felt new, even entertaining. That changed when these robots became part of everyday delivery apps. In some US areas, Serve Robotics now works directly with Uber Eats, and DoorDash has introduced sidewalk robots through partnerships with Coco Robotics.

Once robots appear inside familiar platforms, they stop feeling experimental. People are no longer trying them out of curiosity. They are simply ordering food. The robot becomes part of the service, not the story. As a result, tolerance drops. A late delivery is no longer amusing, and a blocked robot is no longer interesting.

At this stage, autonomous delivery is judged by the same standards as any other delivery system. It is no longer seen as innovation, but as infrastructure that is expected to work quietly and reliably.

The role of AI: smarter robots, same sidewalks

Autonomous delivery robots do rely on artificial intelligence, but not in the way popular narratives often suggest. They do not use general-purpose reasoning systems or creative decision making. Instead, their intelligence is narrow, task specific, and designed to prioritise safety over flexibility.

Most of the AI onboard these robots is dedicated to perception. Computer vision models identify pedestrians, bicycles, curbs, crossings, and obstacles. Machine learning systems classify what the robot is seeing and estimate whether it should slow down, stop, or wait. When situations fall outside predefined confidence thresholds, control is handed over to remote human operators.

In recent years, improvements have focused less on making robots “smarter” in the street and more on optimising decision making around them. AI is increasingly used in fleet management, route planning, incident detection, and demand prediction. The intelligence that matters most often lives in the control systems supervising dozens or hundreds of robots, not inside the robot navigating the pavement.

This explains a central paradox of autonomous delivery. The technology already uses advanced AI, yet its real-world performance is constrained not by computation, but by the unpredictability of public space. No model, however sophisticated, can easily replace the informal human negotiation that allows sidewalks to function.

The hidden human layer

Autonomous delivery often looks self contained from the outside, but it rarely operates without people in the loop. Most fleets rely on remote operators who monitor multiple robots at once and step in when something breaks the script. A robot that hesitates at a crossing, gets stuck behind roadworks, or cannot interpret an unusual situation is quietly handed over to a human.

This does not remove labour. It reshapes it. One operator can supervise many robots, lowering costs while keeping human judgement available when the environment becomes unpredictable. Autonomy here is not a replacement for people, but a layered system that blends software with constant oversight.

Real world conditions further limit the advantage. Rain, debris, uneven pavements, temporary signage, and seasonal clutter reduce reliability and increase the need for intervention. In poor conditions, the gap between robot delivery and human couriers narrows quickly, sometimes disappearing altogether.

Where this leaves the future

Autonomous delivery works, but only when several conditions align at the same time. Routes need to be short and repetitive. Intervention must be rare. Regulation has to allow operation. Public tolerance needs to hold. Remove one of these elements and the business case weakens fast.

This explains why expansion has been uneven. Campuses, residential developments, and carefully selected neighbourhoods continue to support robot delivery. Other places have quietly stepped back.

In Toronto, sidewalk delivery robots were banned entirely, with authorities citing pedestrian safety and accessibility. In the United States, Amazon eventually shut down its Scout delivery robot programme after years of limited trials, acknowledging that the model was not meeting practical needs. None of these outcomes reflect a single technical failure. They reflect environments that were unwilling or unable to absorb the trade offs required.

A technology defined by limits, not ambition

Autonomous delivery is not collapsing. It is settling into its natural boundaries. The future is not robots everywhere, but robots where they make quiet sense. As a layer within logistics, not a takeover. As infrastructure, not spectacle.

The companies most likely to endure are those that treat deployment as urban engineering rather than technological conquest. They choose streets carefully, negotiate with councils early, design around predictability, and accept that autonomy depends as much on cities as it does on code.

Autonomous delivery does not fail because robots cannot move. It fails when public space is unwilling to make room for them. Where space, economics, and social tolerance align, the machines fade into the background. And that quiet normality, more than any promotional video, is what real technological success looks like.

Technology works best when it knows its limits

At Tekaroid, we tend to be sceptical of futures that promise efficiency without asking who they are meant to serve. Robot delivery has shown that technology can move faster than cities, and that autonomy works best when it stays within clear limits. Sidewalks may not be the ideal playground for machines, even if the idea once felt inevitable.

If robots truly want a home, they might find it closer to hospitality than logistics. Restaurants, hotels, and controlled indoor environments offer structure, predictability, and fewer social negotiations. Still, even there, most people would agree that a good waiter understands timing, mood, and human presence in ways no robot can replicate.

Where delivery robots may genuinely shine is not in replacing service, but in supporting independence. For elderly people or those with reduced mobility, reliable local delivery can mean fewer barriers and more autonomy in everyday life. Used carefully, and in the right contexts, these machines are less about the future of work and more about the future of dignity.

As with many technologies we explore at Tekaroid, the question is not whether robots will exist, but where they belong. And the most successful answers are usually the quiet ones.