Kitchens have routines, recipes have steps, and cooking looks repeatable from the outside. If machines can drive cars, why would they not run a kitchen? At Tekaroid, we love imagining possible future scenarios. So here we go!

The answer is not a simple yes or no. It depends on what kind of cooking we mean, what kind of kitchen we mean, and what we think intelligence really is. Because most of what a good chef does is not knowledge. It is judgement under pressure, in a world that refuses to stay stable.

The dream of automated cooking

Automation sells a dream of calm. A machine does not get tired. A machine does not forget a step. A machine does not panic when the printer keeps spitting tickets and the pass is full. If cooking is just inputs and outputs, then it is the perfect candidate for automation.

This promise becomes even stronger when you look at the modern kitchen as a system. A service is a flow of tasks. Prep becomes portions. Portions become timing. Timing becomes consistency. In that logic, the chef starts to look like the weak link, the human variable that introduces error.

That framing is not silly. It is how industrial thinking works. Standardise the environment, reduce variation, and you can automate almost anything. The question is whether real kitchens can ever become that stable without losing what people actually pay for.

A brief history of kitchen automation

Humans have always tried to reduce effort, save time, and make results more reliable. The first wave was mechanical: grinders, mixers, ovens with better control, temperature probes, refrigerators that changed everything.

Then came a second wave: devices that started to combine multiple actions into one workflow. Food processors compressed time. Sous vide compressed risk. Induction compressed heat control. Each tool did not replace cooking. It reduced one form of uncertainty.

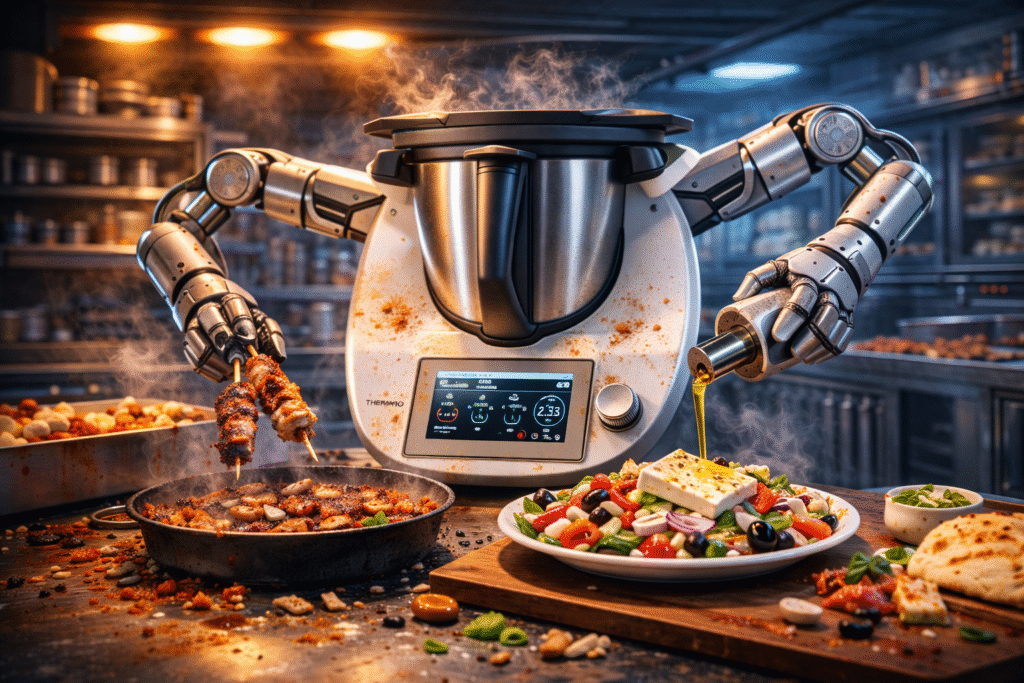

This is where Thermomix sits culturally. It is often presented as a futuristic replacement for skill, but it is better understood as a stability machine. It weighs, heats, stirs, blends, and holds temperature with a level of repeatability that most people cannot match on a busy Tuesday night. It does not replace a chef. It replaces several small points of failure.

The lesson is simple. Most successful kitchen technology does not try to simulate a human. It tries to remove the worst parts of human limitation: distraction, imprecision, inconsistent heat, inconsistent timing.

What cooking robots can already do

If you search for cooking robots, you quickly find two very different worlds. One is domestic, built for convenience. The other is commercial, built for scale. The commercial world is where automation already has real power.

Robots are strong when the environment is engineered for them. High volume kitchens with narrow menus are perfect. A robot can dispense consistent portions, flip burgers, manage frying times, and repeat the same motions for hours. This is not science fiction. It is the logic of automation meeting a stable process.

In practice, many so called cooking robots are not full robots. They are robotic systems. They automate one part of a pipeline: a fryer station, a beverage station, a pizza assembly line, a bowl building line. That is enough to change labour needs, reduce training time, and reduce variability.

What they rarely do is interpret. They execute. They follow a limited set of rules inside a controlled space. That is why the most successful automation tends to appear where the product is already standardised and the kitchen is already designed like a factory.

Where automation starts to fail

The kitchen looks predictable until you work in one. Then you realise it is a live environment full of minor chaos, like for example those ingredients change day to day, a supplier switches brands, a batch of onions is sharper, fish is wetter or steak has different fat distribution. Also can be the sauce, that reduces faster because the humidity changed or a pan behaves differently because it is not the same pan, or simply because is old.

Humans adjust without thinking. A chef does not measure every correction. They taste, watch, listen, and modify. They move heat, change timing, and compensate for variability. That is not just skill. It is pattern recognition trained by exposure to endless small deviations.

Service adds another layer. Timing is not a recipe step, it is coordination. A chef is constantly synchronising multiple processes while handling interruptions. A table sends something back. A colleague needs help. The printer spikes. A delivery arrives late. A customer has an allergy. A piece of equipment fails at the worst time.

Automation struggles here because automation hates surprise. Not because machines are weak, but because systems become expensive when they must handle endless edge cases. Most kitchens are edge cases stacked on top of each other.

Can AI understand cooking?

A lot depends on what we mean by AI. Much of what people call AI today is predictive pattern matching. It is excellent at learning correlations from large datasets. It can suggest recipes, adjust cooking times in smart ovens, optimise scheduling, and reduce waste. It can assist planning and consistency.

But cooking is not only a knowledge problem. It is a context problem. Recipes are not truth. Recipes are approximations that assume a certain stove, a certain pan, a certain ingredient, a certain cook, and a certain goal. The same recipe produces different results depending on who makes it, and what they consider acceptable.

A human chef carries a moving target called judgement. They are not trying to follow instructions. They are trying to produce a result that fits a moment. If a sauce tastes flat, they adjust. If a crust browns too fast, they change heat. If the vibe of the restaurant is casual, they plate differently than in a fine dining room.

AI can learn standards. It struggles with taste as a living target. Not because taste is mystical, but because taste is physical, social, and situational. Cooking is intelligence distributed across all senses, timing, memory, teamwork, and pressure.

The real reason chefs are hard to replace

If you want the most honest answer, it is this: chefs are not just cooks. In many kitchens, a chef is a problem solving engine. The job is not primarily to follow a plan, but to keep the system producing good outcomes while conditions change.

That is why replacing a chef is not like replacing a calculator. It is more like replacing a manager, a quality controller, a mechanic, and a crisis coordinator at the same time. The output is food, but the core skill is handling uncertainty.

There is also an economic reality. Humans absorb complexity cheaply. A trained chef can adapt to hundreds of micro problems without new hardware, without software updates, and without engineering support. A robot that can do the same needs sensors, cleaning protocols, safety systems, fault tolerance, and an environment designed around it.

In other words, automation is not blocked by imagination. It is blocked by cost. Automating stable tasks is profitable. Automating chaos becomes a premium project. That is why we see robots first in narrow menus and controlled flows, not in the most complex kitchens.

Automation is not about Tech&innovation, it is about cost

This section could easily belong in our Finance Center. Because the question of automation in kitchens is not just about technology or innovation. It is, mainly, about margins, risk, and cost allocation. AI does not enter restaurants because it is impressive. It enters where spreadsheets allow it.

Discussions about AI in kitchens often focus on capability. Can a machine cook well enough? That question misses the point. The real issue is not intelligence, but economics.

Restaurants operate on thin margins. Labour is expensive, but technology is not cheap either. A human chef may be inconsistent, but they are flexible, adaptable, and able to absorb unexpected problems without additional infrastructure. A machine promising consistency must justify itself not in theory, but financially.

Automation only makes sense when certain conditions align. Tasks must be repetitive, the environment stable, and volume high enough to justify the investment. This is why fast food chains and industrial kitchens lead adoption. Their menus are narrow, processes predictable, and variation treated as a flaw.

Most independent restaurants work differently. Their value comes from adaptability, seasonal change, and human judgement. Automating that level of variability is possible, but rarely economical. Each new exception increases system complexity and cost.

There is also a hidden expense often overlooked: risk. Humans notice when something feels wrong. Machines require formal rules, sensors, and safeguards. Each safeguard adds maintenance, compliance, and capital exposure. As kitchens grow more complex, automation shifts risk from labour to infrastructure.

From a financial perspective, the future is not full replacement. It is selective automation. Reducing repetitive work, lowering training costs, and supporting human decision making. Full replacement only becomes attractive once the product itself has already been simplified.

What will actually change in the future

The future is not a robot chef taking over most kitchens. It is a kitchen shaped by assistance rather than replacement.

Sensing will improve. Appliances already monitor temperature and timing. Next comes better feedback: humidity, surface browning, viscosity estimates, and tighter portion control. This is not intelligence in a human sense. It is instrumentation.

Workflows will become more hybrid. Prep tasks such as chopping, mixing, portioning, and cleaning are prime candidates for automation. These tasks are repetitive, time consuming, and physically demanding. Removing them improves efficiency without removing judgement.

Operational AI will also matter more than cooking robots. Scheduling, ordering, inventory forecasting, waste reduction, menu engineering, and training systems will quietly improve kitchen stability. Many restaurants fail not because the food is bad, but because operations collapse under pressure.

In high volume environments, robotic stations will expand. Not one machine that does everything, but multiple systems handling specific tasks reliably. Kitchens will become more modular, more predictable, and closer to factory logic where scale demands it.

The hygiene problem no one likes to talk about

Hygiene is often presented as a strong argument for automation. Machines do not forget to wash hands. Sensors can track temperatures, timings, and cross contamination with consistency. In theory, AI could manage allergens and compliance better than humans.

In controlled environments, this already works. Automated systems can dedicate tools and processes to allergen free production and document every step. In large scale food manufacturing, this is a real advantage. The problem appears in real kitchens.

Food environments are harsh. Grease, moisture, heat, and constant cleaning are not side issues, they define kitchen life. Any robot handling food must be cleaned frequently, thoroughly, and in ways that satisfy regulation. That cleaning creates downtime, labour, and complexity.

The more complex the machine, the harder it is to clean. Sensors, joints, and enclosed spaces increase contamination points. Each new component adds surfaces that must be accessed, sanitised, and verified.

Allergen management makes this harder. A system handling multiple ingredients must either clean itself between tasks or duplicate equipment. Both options are costly. Humans, by contrast, are easy to reset. Tools change. Surfaces wipe down. Procedures adapt instantly when an allergy appears mid service.

AI still has a role here, but it is structural. Monitoring, logging, alerts, and enforcement can outperform humans quietly and consistently. Full robotic cooking remains limited not by intelligence, but by sanitation reality.

So, can AI replace a chef?

In some contexts, parts of the chef role can be replaced. Industrial food production is already automated. Chain kitchens can reduce dependence on skilled labour through robotics and standardisation. In fast casual environments, fewer trained cooks may be needed.

But in most restaurants, a chef is more than a cook. They adapt, judge, coordinate, and lead under uncertainty. AI can support this role. It can reduce waste, increase consistency, and remove repetitive tasks. It can make kitchens more resilient. Replacing the chef entirely is a much stronger claim.

To do that, a system would need to handle constant variation, sensory feedback, timing across stations, staff coordination, and failure when plans break. That is possible, but expensive and often unnecessary compared to hybrid solutions.

The deeper point is that intelligence is not the same as competence. A system can be intelligent and still fragile in messy environments. Kitchens are messy by nature. They sit at the intersection of physical reality, human expectation, and time pressure.

At Tekaroid, we are less interested in whether machines can cook, and more interested in why some human tasks resist full automation. Cooking is one of them. Not because it is romantic, but because it is chaotic, contextual, and stubbornly real.