Neuralink is not the first BCI project, and it is not the only serious one in human trials. But it is one of the most ambitious attempts to turn a medical-grade brain interface into something scalable. This article explains what Neuralink actually is, where it came from, what has been proven so far, how it compares to other BCI programs, and what realistic future directions look like.

Brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) have a unique way of triggering extremes. On one side: “humans will merge with AI.” On the other: “it will never work outside a lab.” The truth is less cinematic and far more interesting. This is not a movie, this is the real life, the future arriving.

What is Neuralink?

Neuralink is a neurotechnology company developing an implanted brain–computer interface designed to record neural activity and translate it into control signals for external devices. The current clinical program is built around two core pieces:

-A surgical robot (the R1 Robot) that places electrode threads into brain tissue with high precision

-An implanted device (Neuralink refers to it as the N1 Implant in its clinical trial materials)

Neuralink’s first public-facing product concept has been called “Telepathy” by Elon Musk, referring to using neural signals to control a computer cursor and interact with digital interfaces without muscle movement.

Neuralink is trying to build a direct communication link between the brain and a computer. The idea is that your brain signals could do it for you. It is not about reading thoughts like in science fiction. It is about detecting specific patterns linked to intention and converting them into digital commands.

How does a Brain–Computer Interface work?

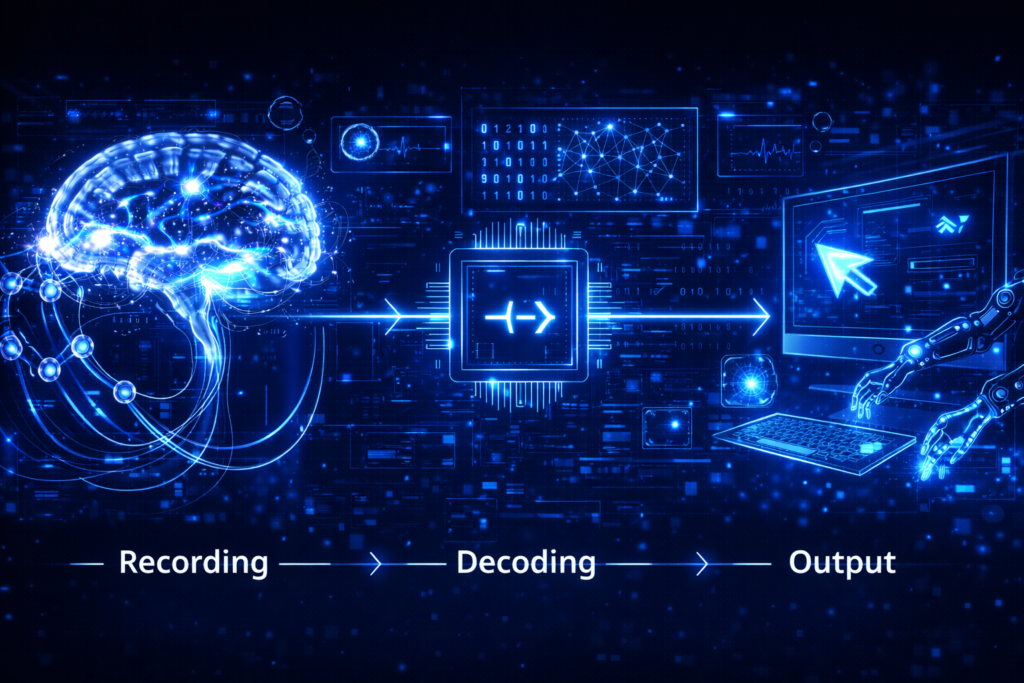

A brain–computer interface detects electrical signals linked to intention, translates them into code, and turns that code into action. What sounds futuristic is a structured engineering process built on decades of neuroscience. It has three layers:

-Output: The decoded intention becomes an action (cursor movement, clicking, typing, controlling assistive tools)

-Recording: Electrodes detect electrical activity produced by neurons

-Decoding: Algorithms interpret patterns (often linked to imagined movement)

The idea is simple: many people with paralysis still generate the intention to move. The BCI reads that intention directly from the brain and routes it around damaged pathways.

This concept is not new. Research programs like BrainGate have demonstrated cursor control and device interaction with implanted arrays for years.

Why Neuralink matters

Neuralink is not just another tech headline. It sits at the intersection of medicine, engineering and regulation, where experimental neuroscience begins to collide with real-world clinical systems. Understanding why it matters requires looking beyond the hype.

-Clinical potential for paralysis and communication: Human trials focus on people with severe paralysis, aiming to restore digital independence (communication, computing, control of devices)

-Engineering ambition: Traditional intracortical BCIs have often been research-grade setups with external hardware. Neuralink is pushing for a fully implanted, wireless system and robot-assisted implantation—which matters if the technology is ever to leave small, specialist labs.

-The sector is accelerating: The FDA (Food and Drug Administration) and NIH (National Institutes of Health) have publicly treated implanted BCIs as an emerging clinical category that needs better outcome measures and standards, which signals the field is moving from isolated experiments toward medical evaluation frameworks.

BCIs before Neuralink

euralink did not invent brain–computer interfaces. By the time it appeared, the field already had decades of experimental progress behind it. Programs such as BrainGate began clinical trials in the mid-2000s and demonstrated that people with paralysis could control a cursor or external devices using implanted electrode arrays. Long-term data collected over nearly twenty years has shown both the remarkable potential of these systems and the persistent technical challenge of maintaining stable neural signals over time.

Other companies built on that research foundation. Blackrock Neurotech, for example, has been closely associated with implantable electrode technology and clinical-grade neural recording systems. Its MoveAgain platform received FDA Breakthrough Device designation in 2021, signaling that regulators viewed implantable BCIs not as speculative experiments but as emerging medical tools with defined therapeutic goals.

The shift in the 2020s has been less about proving the concept and more about engineering viability. The focus has moved toward wireless systems, reduced surgical complexity, and making BCIs usable outside tightly controlled research labs. In that broader transition from demonstration to deployable medical product, Neuralink is one contender among several, not the origin of the field itself.

Neuralink timeline: How it started and where it is now

Neuralink was founded in 2016 and spent its early years developing surgical techniques and implant hardware through animal research. In 2022, human trials had not yet been approved at that stage, reports indicated that the FDA had raised safety concerns in an earlier application process, including questions about implant safety and removability.

The turning point came in May 2023, when Neuralink received an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from the U.S. FDA, allowing it to begin clinical testing in humans.

In January 2024, the company announced its first human implantation and later shared updates showing participants using neural signals to control a computer cursor.

By 2025, a first UK implantation was reported at University College London Hospitals, where a patient was able to interact with a computer shortly after surgery.

In 2026, Neuralink published a “Two Years of Telepathy” update outlining surgeries performed across 2024 and 2025, suggesting gradual clinical scaling and iterative improvements. Public statements have also pointed toward ambitions for higher production capacity and greater automation. Still, it is important to distinguish between milestone announcements and peer-reviewed clinical evidence. Early feasibility studies mark progress, but they remain the beginning of a much longer medical validation process.

What Neuralink can really do

The device does not read thoughts in full sentences or interpret emotions, just detects electrical patterns linked to the intention to move.

Those signals can then be translated into something practical, as for example, basic computer tasks. For a person with severe paralysis, that is not a novelty, is communication that means independence and access to the digital world without muscle movement.

But not everything is perfect, many popular assumptions remain far ahead of reality, Neuralink is not uploading memories and is not enabling brain to brain messaging. The clinical goal today is much narrower and much more concrete. Build a stable system that converts intention into digital control. In medicine, that kind of precision matters more than spectacle.

Other BCI projects

In this field, not all is about Neuralink. Different companies are working on this technology, like for example, Synchron that they are testing less invasive, vessel-based implants, while others such as Precision Neuroscience and Paradromics are exploring surface or high bandwidth cortical approaches. Also Blackrock Neurotech builds on long clinical research roots and a more traditional clinical pathway.

The real difference between them is not the idea of connecting brain to computer, because that already exists. It is about trade-offs: how invasive the surgery is, how clear the signal becomes, and whether the system can work safely outside a lab. In other words, this is not a single breakthrough story. It is an engineering competition.

Technical challenges

Making a cursor move with brain signals is impressive, but it is only the beginning. Even if cursor control works, BCIs must overcome several hard realities:

-Signal stability over time: One of the hardest problems is long term signal stability. The brain is not a fixed object. It shifts microscopically, tissue responds to foreign materials, and electrodes can degrade over time. Research from earlier implanted systems has shown that maintaining reliable signals for years, is one of the biggest engineering challenges in the field.

-Surgical safety: Surgery is another critical factor. If this technology is ever to move beyond small experimental groups, implantation must be consistent and safe across many patients. The strategy of Neuralink relies heavily on robot assisted placement to improve precision and repeatability. The question is not just whether the device works once, but whether it can work reliably at scale.

-Training, calibration, and usability: May matter more than raw performance. A strong neural signal is meaningless if the system requires constant recalibration, complex setups, or a team of technicians to operate. The real product is not just the implant inside the skull. It is the entire ecosystem around it.

Ethical and security questions

When you place technology inside something as complex as the human brain, challenges are inevitable. In a system this sensitive, unexpected risks and difficult questions naturally appear.

-Privacy of neural data: Neural signals are not ordinary biometrics. They can reveal intent and patterns tied to identity. Ownership, storage, and governance become essential design decisions.

-Cybersecurity: A wireless implant is a cybersecurity surface. Even if the risk is low today, it must be treated as serious by design, not as an afterthought.

-Regulation: The field is actively working on how to demonstrate benefit in implanted BCIs—what outcomes actually count, and how they should be measured.

-Access and inequality: If BCIs become effective, access will not be evenly distributed. First it will be medical (and expensive). Later, if enhancement ever arrives, inequality could become structural in new ways.

Because of that, the real test of this technology will not be how futuristic it looks, but how responsibly it is built and governed over time.

What Neuralink plans to do next

Neuralink has expanded its clinical activity beyond its first implantation, adding more participants and additional surgical sites. The emphasis now appears to be on accumulating structured clinical experience.

Public reporting has also referenced feasibility work involving assistive robotic devices, pointing toward ambitions that extend beyond cursor control and into interaction with the physical world.

Statements cited by Reuters have described goals around higher production capacity and more automated surgical processes. These ambitions are not clinical validation in themselves, but they signal a transition from experimental phase toward an attempt at building a medical system.

Conclusion: Brain becomes infrastructure

If BCIs reach the point of working reliably, the shift will go beyond convenience. This is not just about typing faster or removing a keyboard. It is about turning the brain into an interface layer for digital systems. That represents something deeper: the mind moving from being only the source of decisions to becoming a direct input channel.

For now, the focus is medical and practical. Helping people communicate is not science fiction — it is rehabilitation. But as the technology improves, harder questions will follow: who gets access, how it is regulated, and where the limits should be.

By 2026, brain–computer interfaces are no longer just an idea. They are becoming an industry. The real issue is not whether they look impressive, but whether we are building the rules and safeguards as carefully as the hardware itself.

Brain–computer interfaces are only one part of a much larger transformation. Explore how AI and digital infrastructure are affecting society in Tekaroid.